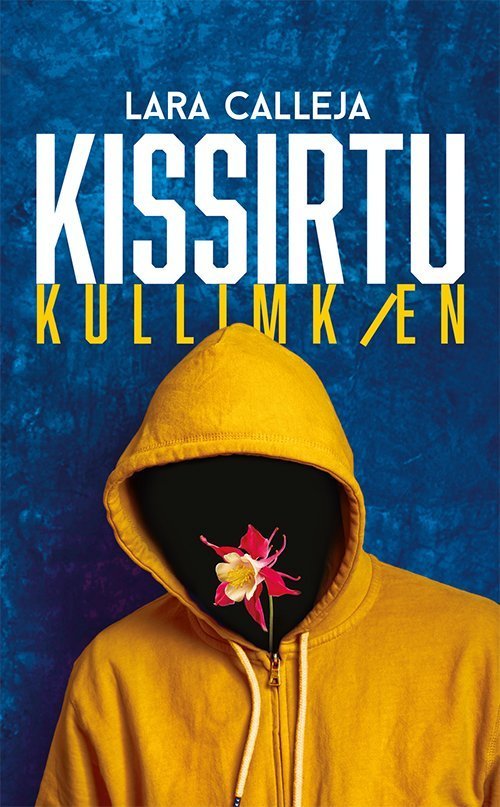

Lara Calleja, born in 1988, was raised in Marsaskala, a once quaint seaside village in Malta that is now overshadowed by apartment blocks. Having graduated with honours in Near Eastern studies in 2010, Calleja worked for several years in tourism. Her debut novel, Lucy Min?, was published in 2016 and shortlisted for Malta’s National Book Prize. Calleja then worked as a part-time librarian for 6 years, finding an outlet for her love of books. She loved organising yearly literary events and she managed to upgrade the collection of the very small library that employed her, leading to an increase in readership at a time when use of Malta’s public libraries was diminishing. Having continued to write during this time, in January 2020, Lara left her full-time job in tourism to start her career as a freelance writer and translator. In the following months, she published her second book, Kissirtu Kullimkien (You've Destroyed Everything), which won her the National Book Prize for best emerging author. In the summer of 2020, Lara was commissioned to write her first-ever theatrical script. Her play Taralalla will be staged at Valletta’s art hub Spazju Kreattiv in October 2021.

Agent / Rights Director

Publishing House

Excerpt

Kissirtu kullimkien - Lara Calleja - Language: Maltese

Rożi tax-Xgħajra

Rożi

Rożi ftit kienu jafuha nies. Rari ħarġet mir-raħal ħlief għal xi tieġ jew festin tal-familja. Li toħroġ ’il bogħod minn raħalha għal Rożi kienet xi ħaġa kbira. Kienet tħoss diqa enormi, qisu xi ħadd ċaħħadha minn element bażiku ta’ ħajjitha, u għal dawk il-ftit sigħat li kienet tqatta’ ’l bogħod mix-Xgħajra, Rożi kienet itteftef fil-libsa u tħossha kemxejn aġitata, b’ġenn inkallat biex in-neputi Liam jegħja jixrob u jfittex iwassalha lura d-dar. Ir-raħal tax-Xgħajra Rożi kienet tħobbu wisq. Xi trid iktar? Kwiet, baħar li kważi dejjem imqalleb biex jiffriskalek il-pulmun, knisja ħelwa u żgħira u l-istess erba’ wċuħ, li forsi sindikajri xi naqa kemm, imma wara kollox kulħadd sindikajr, hemm min b’ħanġra u hemm minn b’sikta. Finalment Rożi tberikhom għal ġieħ kemm-il darba sabithom fil-bżonn u r-residenti tal-villaġġ tagħha kienu raġuni oħra kbira għalfejn Rożi qatt ma kienet toħlomha li titlaq minn hemm. Tiftakarha kuljum meta missierha tah attakk ikrah f’qalbu. X’kienet tagħmel mingħajrhom li kieku f’dik il-ġimgħa ma ħadux paċenzja biha? Iwassluha Mater Dei, isajrulha, u jitimgħulha lil Ġovanna, il-qattusa ndannata u nofs grazzja li żżomm f’darha Rożi.

Ix-Xgħajra villaġġ żgħir u ftit huma n-nies li jgħixu hemmhekk matul is-sena kollha. Ħafna kienu jiġu għal sitt xhur biss, igawdu x-xatt kwiet. Fix-xitwa, il-maltempati u l-irwiefen hemmhekk huma xi ħaġa fenomenali; ir-riħ tistħajlu xi kelb irrabjat qiegħed iħuf wara t-twieqi ta’ darek, u l-baħar jogħla s-sulari sakemm fl-aħħar jispiċċa jitfarrak waħdu mal-blat xieref. B’hekk ħafna jiddeċiedu li fl-istaġuni iktar kesħin idabbru rashom lura lej’ darhom f’Ħaż-Żabbar.

Imma Rożi, sajf u xitwa hemm. Dejjem. Għalkemm ma kinitx toqgħod fejn il-baħar, kienet ixxomm dik ir-riħa ta’ ilma mielaħ minn kullimkien. Magħmul minn diversi niżliet paralleli, li kollha jagħtu għax-xatt, il-baħar fix-Xgħajra tarah, tħossu fi mnifsejk ma’ kull kantuniera.

Imma mhux din l-aħħar sena. Minn meta waqqgħu d-dar ta’ ħdejha, u dik li tmiss mal-parapett ta’ wara — hekk, kollha f’daqqa — Rożi ma tafx x’laqatha. Flok riħa ta’ melħ ma’ kullimkien, hemm riħa ta’ terrapien u ġir. Flok ħsejjes tal-bejta għasafar fir-rebbiegħa jħaxwxu xi mkien mas-siġra tal-larinġ fil-ġnien, hemm ħoss ta’ jigger li jtaqqablek il-voglia li tgħix il-ġurnata. Flok jilqgħek ir-raxx sabiħ tal-baħar dejjem imċaqlaq tax-Xgħajra hekk kif tiftaħ l-antiporta (li issa qed tkun rarament miftuħa), tilmħek daħna bajda ta’ trab tat-tfarrik ta’ ġebel, li tidħollok f’għajnejk.

Il-qattusa Ġovanna wkoll qisha mhix f’postha. Qabel bilkemm kont taraha ġewwa. Dejjem moħbija xi mkien fis-siġra tal-larinġ — daqqa rieqda hemm, daqqa tiżvoga difrejha ma’ zkukitha, u daqqa biex mingħaliha ħa tħebb għal xi għasfur tal-bejt. Imma issa Ġovanna dejjem rieqda fuq is-siġġu ta’ ġewwa, u bilkemm titħarrek ħlief meta tisma’ ċ-ċekċik tal-ikel. Donnha saret iktar fessuda wkoll. Sforz id-dwejjaq ta’ dak li qiegħed jiġri madwarha forsi — jew abbli qed tixjieħ u timmansa, taħseb Rożi. Jew sforz it-tnejn insomma. Min jaf.

Taħdita tal-istess erba’ wċuħ —

“Xi ġmiel Marì, rajthom t’hemm isfel?” “Xiex?”

“Tellgħu blokka. Ta’ fuq nett jaraw il-baħar.” “Ija mela. It-tifla ta’ Marju xtraw wieħed. Ma ħaduhx daqshekk ta. Mitejn elf. Bil-madum u l-kmamar tal-banju.”

“Il-Marija Madunna. Id-dar tagħna qrib l-għaxart elef konna xtrajnieha tletin sena ilu. U tara l-baħar.”

“Ijwa Tes ħi, imma għaż-żminijiet t’issa mitejn ċuċata ħaduh.”

“Ija vera, forsi. Sbieħ ħafna insomma. Għidilha r-risq ħija.”

“Qed itellgħu ta, mhux ħażin. Issa anke ta’ Rożi qed iwaqqgħu.”

“Ija?”

“Mela.”

“U Rożi? Ili ma naraha kos.”

“E, Rożi l-Imgieret ħija. Kienet ilha bilkemm tista’ timxi miskina, imma qatt ma tħajret iddabbar rasha mix-Xgħajra dik. Dejjem hawn taraha. Itteftef xi ħobża fuq il-banketta. Ħa ngħidlek, aħjar Alla joħodni milli nispiċċa f’dik l-imniefaħ dar tax-xjuħ. Ommi kienet hemm, Alla jaħfrilha. Qisha dar tal-imġienen ħi mhux dar tal-anzjani. Jittrattawk qisek tifla ta’ sitt snin, u bilkemm iħalluk toħroġ.”

“Miskina Rożi. U d-dar min ħadha allura?” “Ħuha ħi għandikun. Dik għandha ħuha xi għoxrin sena iżgħar minnha u ħa d-dar f’idejh u waqqagħha. Qed jistennew il-permess għal sular ieħor, qalli Twanny.”

“Issa ngħid lit-tifla ta’ oħt Joe, għax dik kienet qiegħda titħajjar tixtri flett lejn dawn in-naħat.”

Ġovanna

Għadni qiegħda nħuf fiż-żibel li donnu dal-aħħar qed jiżdied fl-inħawi, bit-tama li nsib xi sidra ta’ tiġieġa bħall-aħħar darba. Imma minflok kelli nerġa’ nqatta’ lsieni ma’ ħaġa tonda li kellha xi fdalijiet ta’ xi tip ta’ ħuta. Hemm tfajla ġieli tiġi ttini xi ħaġa tal-ikel, imma mill-bqija rrid infendi għal rasi biex immantni ruħi. Minn għajnejja l-ħin kollu ħierġa żlieġa u ġieli juġgħuni u ma nkunx nista’ niftaħhom sew. Dal-aħħar ukoll l-għasafar bilkemm għadni nismagħhom. Eħħħ. Dak iż-żmien tas-siġra kollha blalen oranġjo, u l-ikel dejjem lest u s-sodda dejjem sħuna, spiċċa. Dik ix-xwejħa tal-ġersi kulur is-sema u għajnejn kulur il-ħamrija, għebet bla ma biss qaltli ċaw jew avżatni li f’daqqa waħda ħa nispiċċa bla saqaf fuq rasi.

Jien naħseb ħadha miegħu xi mkien dak ir-raġel ikrah li darba fost l-oħrajn lestieli platt bl-ikel favorit tiegħi. Jien għedt da’ kemm ħa naqla’ ikel illum? U sa anke ħariġli l-plattina fil-parapett tan-naħa l-oħra li qatt ma kienet tħallini noħroġ fih dik il-mara tal-ġersi kulur is-sema. U jien u niekol bil-qalb, ir-raġel ikrah bi qmis kulur il-plattina għalaq il-bieb minn fejn kont ħriġt b’sabta, u bqajt maħsuda nħares lejh jgħaġġel ’il bogħod sakemm ma deherx aktar. Stennejt lilu jew lill-mara tal-ġersi b’kulur is-sema biex jerġgħu jfeġġu ħalli jiftħuli l-bieb. Wara tlett ijiem nistenna, iċċaqlaqt minn hemm, u bdejt inħuf għal rasi, bit-tama li l-mara ta’ għajnejha kulur il-ħamrija terġa’ tiġi lura, u tiftaħli l-bieb għal ġewwa.

Imma meta għadda naqa żmien u rajt qisu annimal ikrah u enormi jiddevora lid-dar fejn darba kont ngħix, sa anke rajtu jqaċċat lis-siġra kollha blalen oranġjo minn għeruqha; qtajt jiesi għalkollox u dakinhar u anke l-għada marli l-aptit għalkollox li niekol jew niċċaqlaq.

Meta tkun trid tmut fix-xjuħija, il-ġisem iċedi u jħallik tmut

Dakinhar li nbiegħ l-ewwel flett fejn darba kienu jimirħu omm, missier, ħut Rożi u l-qattusa Ġovanna, Rożi ħadet l-aħħar nifs imqanżaħ f’waħda mir-ringieli sodod bojod u minsijin tal-Imgieret.

Rożi kienet ilha titlob lill-Bambin tal-Ħniena Divina biex joħodha miegħu u jeħlisha mit-torment ta’ din il-ħajja ġdida li qatt ma basret se tiġi imposta fuqha proprju fl-aħħar żmien ta’ ħajjitha. Ġieli kienet taħseb f’Ġovanna. Fit-tliet darbiet li ġie jżurha ħuha ż-żgħir, qatt ma rnexxielha toħodlu minn rasu x’kien għamel biha. Imma ħarstu kien idawwarha n-naħa l-oħra u Rożi fehmet li bħalma rema lilha f’dan l-isptar ikrah fejn qatt ħadd ma jiġi jżurha, ma kienx ħa jiddejjaq jarmi lil Ġovanna wkoll.

Hawnhekk fl-Imgieret ma kienx postha, kienet tgħid Rożi bejnha u bejn ruħha. Vera li meta kienet tgħix f’darha x-Xgħajra bilkemm kienet tiflaħ timxi, imma mill-bqija kienet tħossha tarmi s-saħħa. Ġara mbagħad imma li bil-bini u l-istorbju u kulma kien hemm madwarha, ħuha ż-żgħir fl-aħħar irnexxielu jikkonvinċiha li aħjar tinġabar xi mkien fejn jistgħu jieħdu ħsiebha. Xi mkien sabiħ fejn hemm ħafna siġar u kwiet. U lil Ġovanna joħdilha ħsiebha hu. Tħabbilx rasek, kien jgħidilha. Waqgħet fin-nassa. Pu!

Hekk kif Rożi kienet fis-sodda fl-aħħar ftit sigħat ta’ ħajjitha, in-ners semgħetha tgedwed u tgħid ħafna affarijiet. In-ners tħassritha waħedha u qabdet siġġu u poġġiet ħdejha. Fl-esperjenza tagħha kienet taf li dawn huma sinjali li jimmarkaw l-aħħar ftit sigħat ta’ persuna qiegħda tmut.

“Miskina, waħedha ħallewha u qgħadt ħdejha jien. Imma kellha tbissima kbira fuq wiċċha u bdiet tgħajjat lil xi ħadd Ġovanna biex tinżel mis-siġra ħa tagħmlilha l-ikel. Qabbditni l-bard kif bdiet titbissem u taqleb għajnejha fl-istess ħin. Imbagħad qabditli idi u staqsietni jekk irridx melħ mal-brodu. Komplejt magħha u għedtilha iva u mellistilha rasha. Staqsietni jekk hix qiegħda x-Xgħajra u kont naf li kienet tħobbu ħafna hemmhekk, taf int kibret hemm u kulħadd jafha mid-dehra. U jien għedtilha iva, ix-Xgħajra qiegħda, u Ġovanna qiegħda hawn ħdejja. Wiċċha sserja f’daqqa u staqsietni jekk Ġovanna ħafritilhiex. Ma nafx min hi di’ Ġovanna jien, imma għedtilha iva mela ħafritlek.”

Reġgħet tbissmet Rożi u baqgħet b’ħalqha kemxejn imċarrat hekk. U n-nifs beda jbatti bil-mod ma’ kull minuta sa ma ħadet l-aħħar nifs.

Forsi wara m’hemm xejn, hemm baħħ, kif jgħidu ħafna. Imma ddeċidejt li nemmen li Rożi wara mewtha marret lura f’darha x-Xgħajra, fir-riħa tal-larinġ, mal-ħoss tant għal qalbha tar-riħ isabbtilha mal-antiporta u ma’ Ġovanna rieqda fuq is-siġġu tal-kċina.

Excerpt - Translation

Translated from Maltese by Clare Vassallo

Rożi from Xgħajra

Rożi

Not many people knew Rożi. She very rarely left her village, and then only for some wedding or family party. Spending time away was a big deal for Rożi. It distressed her, made her feel as though some basic right in her life was being denied, and the few hours that Rożi was away from Xgħajra were usually spent with her fiddling with her dress and battling feelings of anxiety as she waited with increased desperation, for her nephew, Liam, to decide he’d had enough to drink and get round to driving her back home. She loved that little village of Xgħajra so very much. What else could one desire? Tranquillity, the sea, which was always just restless enough to freshen your lungs, a pretty little church, and the same bunch of people who were, perhaps, a little nosey but, then again, most people are a little bit curious - it’s just that some express it at the tops of their voices while others do it in whispers. Most of all, Rożi blessed them for their help and for the kindness shown to her whenever she was in need. Those villagers were in fact another important reason why Rożi would never dream of moving away from there. She always remembered the day her father suffered a massive heart attack. How would she have coped if they hadn’t patiently helped her out? They drove her to Mater Dei Hospital, cooked for her, and fed Giovanna, the crazy clumsy cat that lived with Rożi in her house.

Xgħajra is a small village and very few people live there all year round. Most people only come for six months of the year to make the most of the peaceful seashore. In winter the storms and gale force winds are extraordinary: the wind can sound like an angry wild dog on the prowl outside your window, and the waves rise as high as buildings until they finally smash and disintegrate against the sharp rocks. This is why most people decide to return to their homes in Ħaż-Żabbar for the colder months.

But not Rożi – she spends all her summers and winters there. Always. And although she does not live quite at the water’s edge she can smell the spray of salty water from everywhere. The village, made up as it is of a few parallel hills which all converge down at the shore, means that sea in Xgħajra is visible from all around and can be felt nice and fresh in your lungs from every corner.

But not this last year. Ever since the house next door to hers, together with the one which came right up to wall surrounding her backyard, were pulled down – just like that, both at the same time – Rożi doesn’t know what’s hit her. Instead of the scent of sea-spray in the air, there’s dust from rubble and lime. Instead of the rustling sounds in spring from birds’ nests in the orange tree in the garden, there’s the excruciating sound of a digger that destroys your very will to survive the day. Instead of the welcome spray from the choppy sea hitting you when you open the front door (which she rarely keeps on the latch anymore), a white cloud of fine dust greets you, and enters your eyes.

Giovanna the cat also feels uneasy. She barely used to spend time indoors before. She was always tucked away somewhere in the orange tree – sometimes fast asleep on a branch, sometimes sharpening her nails against the trunk, and sometimes actually believing she might catch a sparrow. But now Giovanna is always fast asleep on a chair inside the house, and she barely bothers to move except when she hears the rattling sounds of her food being prepared. She seems to have become more affectionate, too. Possibly due to boredom caused by what’s going on around her – or perhaps because she’s getting older and meeker, thinks Rożi. Or maybe a bit of both. Who knows.

Conversation between the same few people…

“How beautiful Marì, have you seen the ones over there?”

“What?”

“A block has gone up. There are sea views from the top ones.”

“Yes, of course! Mario’s daughter bought one of them. It wasn’t too expensive, you know. Two hundred thousand. That’s with floor tiles and bathrooms included.”

“Madonna! Our house only cost eleven thousand about thirty years ago. And we can see the sea.”

“O yes, Tessie hun, but for these days they got it for a song.”

“Yes, well, maybe. They’re quite lovely really. Wish her luck, will you?”

“There's quite a few new buildings coming up now, you know. And even Rożi's house has just been pulled down.”

“Really?”

“Yes, for sure.”

“And Rożi? In fact I haven’t seen her in ages.”

“Well, Rożi’s at the Imgieret Home now. She could barely walk anymore, poor thing, but you know, she never wanted to leave Xgħajra. You’d always see her around. Sitting on a bench and snacking on a piece of bread. Let me tell you, I’d prefer God to take me a little earlier than ending up at that awful old people’s home. My mother was there, God rest her soul. It’s more like a madhouse than an old people’s home. They treat everyone like little children and hardly ever let you out.”

“Poor Rożi. So who’s taken her house then?”

“Her brother, I think. She’s got a brother who’s about twenty years younger and he’s taken over the house and had it pulled down. They’re just waiting now for new permits to be able to add an extra floor, that’s what Twanny said.”

“OK, well I’ll tell Joe’s sister’s daughter about it. She’s thinking of buying a flat around here.”

Giovanna

I’m still hunting for food in the rubbish which really seems to have increased around here recently. I was hoping to find some chicken breast like last time, but instead I ended up cutting my tongue again on a round thing which had the remains of some kind of fish on it. A young girl comes to feed me sometimes, but mostly I have fend for myself. My eyes are constantly watering and blurry and they sometimes hurt so I can’t open them properly. I hardly hear the birds any more, either. Ahhh … those days in that tree of orange balls, food always ready and waiting, and a warm bed for the night have well and truly gone. That old woman in a sweater the colour of the sky and eyes the colour of soil has disappeared without even saying goodbye or warning me that I was about to find myself without a roof over my head.

I think that horrible man must have taken her away with him. He once prepared a plate of my favourite food. I wondered to myself how much food I would be given that day. He even brought the plate out into the backyard where the woman in the sky blue top never allowed me to go. As I was digging into it, the ugly man in a shirt the colour of my plate slammed the door. I was stunned as I watched him scurry away until I couldn’t see him anymore. I waited for him or the woman in the sky blue top to hurry back and open the door for me. After three days of waiting, I moved on from there and began to hunt for my food, always in the hope that the woman in the sky blue top would return, open the door and let me in.

But when some time passed and this monstrous animal turned up and devoured the house where I once lived, even pulling up the tree with the orange balls from its roots, I realized it was all over and that day, and the next – I completely lost my will to eat or even to move.

When you want to die in old age, the body gives in and allows you to die.

Rożi took her final rasping breath on one of those white forgotten beds in rows at the Imgieret Home precisely on the day that the first flat, built where once Rożi’s mother, father, siblings and Giovanna the cat lived, was sold.

Rożi had for some time now been praying to Jesus of the Divine Mercy to take her with him and release her from the torment of this new life which she never imagined would be imposed upon her precisely at the end. She often thought of Giovanna. During those three visits of her brother she never managed to prise out of him what exactly he’d done with her. He just looked away, and Rożi understood that just as he’d dumped her in this ugly home where no one ever visited her, he wouldn’t have been at all bothered to throw Giovanna out, either.

This Imgieret place just wasn’t for her, she’d tell herself repeatedly. It’s true that when she was still at her house in Xgħajra she could barely walk, but she felt strong and healthy in every other way. What happened was, with the building works and the constant noise and everything going on around her, her younger brother managed to convince her that it would be in her best interest to move some place where she could be taken care of. Somewhere beautiful full of trees and tranquillity. And he would take care of Giovanna himself. Don’t worry, he’d tell her. She fell right into the trap. Pu!

As she was lying in her bed in those last hours of life a nurse overheard her mumbling. The nurse pitied her there, all alone, she pulled up a chair and sat beside her. She’d had enough experience to recognize the signs of a person dying.

“Poor thing, they left her all alone so I stayed with her. But she had a big smile on her face as she called out to someone, Giovanna, to get down from the tree so she could feed her. It gave me the shivers to watch her smile and roll her eyes at the same time. Then she grabbed my hand and asked whether I wanted salt in my broth. I went along with it and said yes as I stroked her hair. She asked me whether she was in Xgħajra and, because I know that she loved it very much over there, you know she was brought up there and everyone there seems to know her, so I said yes. You’re in Xgħajra, and Giovanna is here next to me. Her face got all serious suddenly and she asked whether Giovanna had forgiven her. I don’t know who this Giovanna is, but I said yes of course, she has forgiven you.”

Rożi smiled once more and remained that way with her mouth open wide across her face. Her breathing got shallower and slower with each minute that passed until she took her final breath.

Perhaps there’s nothing after this, an emptiness, as many claim. But I decided to believe that after her death, Rożi returned to her house in Xgħajra, to be surrounded by the scent of oranges, to be within the sound of the wind which she loved and which would sometimes slam her door shut, and with Giovanna fast asleep on one of the kitchen chairs.