Jesús Carrasco was born in Badajoz in 1972. He holds a Bachelor’s degree in Physical Education and has worked, among other things, as a grape-picker, a washer-up, a physical education teacher, a music manager, an exhibition fitter, a graphic designer and an advertising copywriter. He took up writing after moving to Madrid, in 1992. Over the years, he has kept diaries and has written short stories, two books for children and one novel, and has grown as a reader. In 2005, he published an illustrated book for first-time readers, and that very same year, he moved to Seville, where he currently lives.

In 2013, his first novel, Intemperie, made a stunning debut on the literary scene. Carrasco received the Book of the Year Award from the Association of Madrid Booksellers, the Award for Culture, Art and Literature from the Fundación de Estudios Rurales, the English PEN Award and the Prix Ulysse for the best first novel. He was also short-listed for the European Literature Award in the Netherlands, the Prix Médi- terranée Étranger in France and the Dulce Chacón, Quimera, Cálamo and San Clemente awards in Spain.

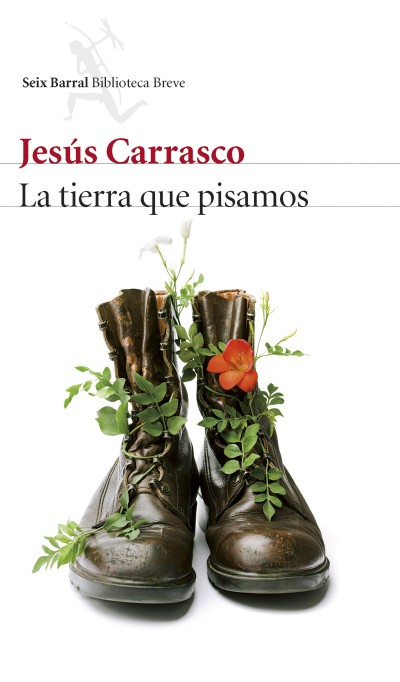

La tierra que pisamos (The Earth We Tread) explores our ties to the land and our birthplace, but also to the planet that supports us. These relationships range from the brutal commercialisation of power to the pleasant emotions of a man tending to his crop in the shade of an oak tree.

And between these two extremes, one woman struggles to find true meaning in her life, a revelation that her upbringing has kept at bay.

In the same rich, precise prose as his previous novel Intemperie (Out in the Open), in this book Jesús Carrasco explores humanity’s infinite capacity to withstand hardship, the revelation of empathy when someone ceases to be a stranger in our eyes, and the nature of a love greater than we are. This is a thrilling read, a book that might just change your perspective on the world.

Agent / Rights Director

Publishing House

Translation Deals

- Albania: Fan Noli

- Bulgaria: Uniscorp

- Croatia: Ocean More

- Czech Republic: Akropolis

- France: Robert Laffont

- Hungary: Typotex Kiadó

- Italy: Salani

- Netherlands: Meulenhoff

- North Macedonia: Tri Publishing Centre

- Norway: Cappelen Damm

- Portugal: Marcador

- Serbia: Heliks Publishing House

- Slovakia: Brak

- Slovenia: Goga

- Sweden: Natur & Kultur

Excerpt

1.

A noise roused me in the middle of the night. Not Iosif’s snoring: strangely for him, he was asleep at my side in silence, half-sunk in the wool of the mattress. I stayed there prone, my gaze resting on the beech wood of the beams supporting the roof, hands clasping and seeking a solidity that the linen, so delicate, denied me. I stayed still some time, shoulders drawn in and hands closed. I wanted to hear the noise again clearly, to pin it on one of our animals, and having done so, to go calmly back to sleep. But I perceived nothing apart from the air rattling the branches of the big holm oak, and then, as if by sorcery, the old myth of the intruder with eyes torn out by greed, took hold of my entrails and set to devouring them.

It’s August, the panes of the guillotine window are hoisted as high as they go, and a balmy, perfumed breeze sways the lace curtains. They dance so beautifully that these days, when I am sleepless, I lean against the headboard and stay there spellbound, watching them quiver like delicate pennants. I inhale the fragrances the air brings with it, which displace, now and then, the stagnant aromas in the room. They come in waves, like the sea leaving onshore the remnants of a wrecked ship. In spring, the tang of the orange blossoms in bloom invades everything, especially at nightfall. The tree invariably sends a messenger days before. Still cool days when all of a sudden a fugitive thread gives notice that there, in some nook in its shadows, life has been summoned to be born again.

With fists full of fabric and eyes shut, I tried to concentrate on the darkness outside. I imagined stepping out onto the porch that presides over the fragrant stretch of grass surrounding the house, and from there I turned my gaze frontward, to where the grounds cut into the valley. In the distance, the gaslights tremble in the village, which is perched like a tortoise on the slopes rising up to the castle. In my mind, I descend the wooden stairs and take a few steps over the damp grass towards the fence that presides over the garden down below. There I hear nothing, not even the coarse chafing of the already withered corn husks.

I turn back to the house to explore the back of the property. Confused forms grow in the flowerpots affixed to the railing on the porch. From the awning, the bell hangs above them, its rope nearly grazing them. The big holm oak ascends to the left of the building, a round, robust creature, its coppice intruding onto the eaves. On the other side, between the dwelling and the road, the small stable with its barred windows and undulating roof tiles. Not even the mare inside is audible, scratching the slate floor with her shod hooves. Nor Kaiser, our dog, but that was to be expected, because he is, without a doubt, the most indolent animal imaginable. “You’d do better to have a hen watch over the property,” the postman said to me once. “Even that one with the frayed neck would be scarier.” And I may have smiled at this notion, and probably said he was right, to get rid of him sooner.

It seems there is a lynx, or a wolf, that’s been marauding for a few days on the outskirts of the village and has killed, so they say, several geese and a lamb or two. Doctor Sneint said as much in the garrison’s dispensary the last time I went to the castle to fetch Iosif’s medicine. While I slipped the phials in my saddlebag, he got up, and after a cursory glance over the spines of his books, he took down an atlas of Iberian fauna and opened it for me. What caught my attention in the etching was the tufted fur hanging by the sides of its mouth and the pointed aspect of its ears. “Paintbrushes, they’re called,” the doctor noted, passing his finger over that part of the print. “Could be a wolf or a fox, though,” he said. “You’ll have to look for its droppings, preferably beside the road to your house.”

“When you find them, open them up and see if there’s much hair inside.” Right then, both the idea of looking for excrement and of breaking it open struck me as repugnant, but on my way home, I found some and couldn’t resist the temptation to poke around in it with a stick. I did not find doing so disagreeable. It smelled of rabbit, and from the look of it, you might say the animal that left it dined on nothing but hair.

I got up and lit the lamp I keep on the nightstand. Leaning out over the windowsill, I moved it from side to side, looking for signs of the animal, but then I realized the full moon glowed brighter than my lamp, and I snuffed it out.

In any case, I found nothing strange. Perhaps my light scared it away. The animals stayed still and I let the warm air coming up from the valley caress my face. The full moon stained the clouds stranded over the flatland a strange yellow. As I fell back to sleep, looking again at the ceiling, it occurred to me there are no beech woods in this part of the country.

I see him for the first time in late morning, while tending the geraniums. The folds of his jacket are there in front of me, poking between the white slats of the fence posts bordering the garden. Next to me, Iosif rests in his rocker, though to say he is resting is, in a certain way, redundant, since he passes the whole day prostrate: in bed, in the armchair in the living room, and for a long spell, here on the porch. I get him up every morning, dress him, and sit him where he’s supposed to go, depending on the time of year. I take him by the elbow, and with short steps he lets himself be led from place to place like a compliant little dog. Illness has reduced him to the merest expression of what he was. A man who had divisions under his command, who held sway over men’s lives, who laid siege to cities and put enemies and traitors to the knife. I ask myself if his old adversaries, those he subdued until making them subjects of His Majesty, hold onto the old fury they must have felt as they rendered up their arms to this man in whose shadow I have lived and whose shadow is now all that I breathe. His mind works in a disjointed manner, and it is just as likely he’ll spend two weeks in silence – head sagging, unable even to lift himself and relieving himself where he sits – as it is likely that he will return, all of a sudden, to reason. In those moments of indefinite duration, he throws himself so wholly into everyday life that it seems as if he’d never left it. Sometimes, he resurfaces like a finicky patient. If we are in the kitchen and he is watching me cut vegetables, he commands me to do so in big pieces, and explains, for the umpteenth time, that he likes to have a sense of what he’s eating. “I don’t want purées, woman. That stuff’s for children, and I’m not a child.”

On occasion, his mind turns to the past and he addresses me as if I were a fragment of memory; he calls me “Commandant Schultz” or “my flower,” with a martial or a honeyed tone, respectively. The strange thing is that never in our lives, even when we were engaged, did he once call me “my flower.” It could be that down in the crevices in his brain, old longings stir, or the recollection of another woman he must surely have yearned for during his long stays away, in the days when the campaigns came one after the other and it seemed the Empire would end up overrunning the whole globe.

Fortunately, it’s been years since the last visit of the man who made my world’s foundations quake. How he would get mad when little Thomas wouldn’t decline correctly, or when he came back stained from the yard. He’d grab him by the ear, pull, and lift the boy almost off the ground. He’d shove him back and forth, and not just a few times, the boy got a backhand or a rap across the fingers with a wooden ruler. I begged him to leave off with it, said he was only a boy, and then he’d turn to me and drown me in the murk of his gaze; the gaze of one who’s drunk his fill of the boiling blood of men. A gaze the memory of which still makes me shiver, and relics of which linger in the depths of his eyes.

“Goddamned borer beetles,” I say to myself, looking at the perforated stalks. They’re impossible to exterminate, and every year I have to pull up bunches of my plants and burn them behind the house, as that’s the only way to keep the plague from affecting the healthy ones. I grab them by the stems and pull them upside down, tearing them out of the flowerpots. The dark soil falls to the ground, always cool and tightly packed, making spongy clods that I bring up to my nose to intoxicate myself with their scent.

I raise my head in search of the vast horizon of Tierra de Barros, and there is his dark jacket, poking through the white boards, filthily invading our property. Kaiser has gone over and sniffs at him, curious, on the near side of the fence.

Without taking my eyes off the man, I stand upright, step back slowly to the open door, and take down the shotgun we have hanging in the entryway. I have to stand up on tiptoe to get to the bandolier with the shells. If the threat had been violent, if instead of this beggar, it had been a thief trying to break into the house, I wouldn’t have had time to fend him off. But I can’t allow Iosif to have a loaded shotgun within reach. Not again.

My fingers tremble while I slide the shell into the barrel. I close the breech, descend the steps, and walk in his direction. At a certain distance, I pause, press the stock into my shoulder, and hope to find myself faced with nothing more than a disoriented drunk against whom, I pray, a broom would be weapon enough.

“You can’t be here,” I tell him. “This is private property.”

He doesn’t respond or move. He doesn’t turn his head to look at me. From this side of the fence posts, all I see is his dirty, dishevelled scalp.

I wait. Kaiser slips his muzzle between the boards and nudges him, like a gentler version of the ever-less patient toes of my shoes. I come a bit closer, nudge him a few times with the stock of the shotgun, and step back. He stays there without moving, and for an instant, I imagine he is dead. I move sideways to the gate that leads down to the garden. I want to be able to see to the other side without closing the distance. He’s a thin man dressed in the dark jacket I already saw and black pants. He’s leaned against the fence posts, legs straight in front of him, head sagging, hands over his thighs with the palms facing up. Beside him, there’s a suitcase, and on top of it, a brown hat. He doesn’t look like a bum or a drunk, and if he hadn’t sat on the ground and smeared himself with dust, he could have worn those clothes almost anywhere.

“You have to go,” I insist, the gun in my arms, and then he does turn in my direction, but still without getting up. On his jaw is a streak of wispy white hair. His shirt’s gone yellow around the neck, the jacket is too big for him.

“I’m not going to give you money.” Kaiser has already laid down behind him, curled up against the man’s kidney, useless as a pouch of wet gunpowder.

There’s no answer.

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| EUPL_2016_ES_Jesus_Carrasco.pdf | 265.6 KB |