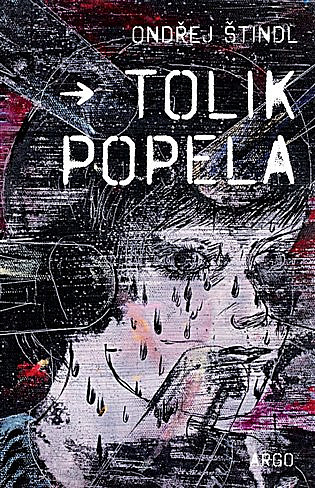

Ondřej Štindl (né en 1966) est critique musical et cinématographique, écrivain, scénariste et DJ. La première du film Pouta (Marche Trop Vite), basé sur son scénario, a lieu en 2010. En 2020, il remporte le prix Ferdinand Peroutka pour son travail journalistique. Il est l’auteur des romans Mondschein (2012), K hranici (À La Frontière, 2016), Až se ti zatočí hlava (Jusqu’à Ce Que Ta Tête Tourne, 2020) et Tolik popela (Tant de Cendres, 2022).

© Picture Agáta Faltová

Ce roman d’Ondřej Štindl, Tant de Cendres, se déroule à Prague dans la première moitié de l’année 2020, lors du début de la pandémie COVID-19. Le livre raconte une histoire incroyable qui représente l’apocalypse comme un symbole d’extinction, mais également comme la promesse d’un nouveau départ.

Le protagoniste du roman, Kryštof Mráz, est saisi par le sentiment d’une urgence nouvelle lors de la pandémie, aussi bien sociale que personnelle. Il est contraint de se poser des questions très fâcheuses et qu’il avait longtemps négligées, de penser au sens de la vie et même à l’existence de Dieu, d’essayer d’accepter sa propre vie et les pertes qu’il a subies, de s’ouvrir à la possibilité de l’amour, d’arrêter de vivre d’une manière « tiède ».

Un écrivain et traducteur vieillissant, Kryštof se trouve soudainement à un carrefour, où il rencontre une jeune intellectuelle gauchiste, Kristýna, et un peu plus tard, Kamil, un gourou qui affiche un lien étrange avec la sœur décédée de Kryštof. La pandémie émergente est en train de changer la vie telle qu’il la connaît, rendant la possibilité de la fin du monde plus réelle que jamais – en fait, Kryštof se dirige peut-être vers une « apocalypse personnelle », en proie à la mélancolie, au grotesque, à des souvenirs intrusifs et à de sombres présages. Il devient un acteur dubitatif dans ce qui est soit l’histoire d’une grande révélation, soit une cruelle blague cosmique. Soit une histoire d’amour.

Excerpt

Ondřej Štindl

Tolik popela

Argo, 2022

Kluk se zastavil uprostřed běhu a mlčky zíral na Kryštofa, rychle dýchal pusou a z nosu se mu pomalu spouštěla nudle. Po cestě od dětského hřiště se zvolna blížila jeho maminka, konverzovala s kamarádkou. Dvě upravené dámy po třicítce v kabátcích pastelových barev a se sladěnými rouškami dodržovaly předepsaný odstup. Praha zvládá pandemii na úrovni alespoň tady, v centru na Petříně, kam se v hojném

počtu dostavilo měšťanstvo a užívalo si slunný jarní den. Radost z pobytu venku, z možnosti promluvit s někým známým se v těch lidech tloukla s přetrvávající opatrností. Nejenom kvůli strachu z nákazy, ale snad i v obavách, aby nedisciplinovaným chováním neohrozili pověst země, kde občané pandemii vzdorují příkladně bez ohledu na odpudivou vládu.

Kryštof ten v jasných barvách vyvedený obraz trochu kazil, pán v uváleném černém oblečení, už dlouho ho nevypral a zjevně nepoužívá ten správný prostředek, tvář zmačkaná a oči zapadlé. Upírá je teď na tříleté dítě, které vypadá, že od něj něco očekává, on ale netuší, co by to asi tak mohlo být. Tak se na kluka usmál, hned si uvědomil, že přes roušku to nebude vidět. V přítomnosti malých dětí byl často v rozpacích, nedokázal shodit dospělou masku a s nelíčenou radostí vydávat infantilní zvuky. Smál se na ně, to jo, nebyl to ale ten reflexivní úsměv, který druhým naskakoval ve tváři pokaždé, když na ně nějaký malý tvor upřel oči. Kryštofovy úsměvy byly vědomé a usilovné, musel si je nařídit, vyslat příslušnou instrukci nervovou soustavou, aby se mu přiměřeně roztáhla pusa. A děcka tyhle jeho nuceně vlídné projevy moc nebaštila. Kluk dál zíral a Martina, která na lavičce seděla vedle Kryštofa, už musela zasáhnout. Střelila po Kryštofovi pohledem a s ironií obrátila oči v sloup. Další nepoužitelnej chlap. Pak se naklonila k dítěti a něco mu říkala, sáhla do kapsy pro tyčinku, tu zdravou s oříškama – jak jinak. Za chvilku už kluk utíkal zpátky k mámě a hlasitě a nadšeně na ni volal. Martina si Kryštofa ještě jednou pobaveně změřila.

„Co je to s tebou, prosim tě?“

„Nic. Dal bych si cigáro. Ale nechce se mi sundavat roušku, když je tu tolik lidí. To je furt něco.“

Martina se zasmála, trochu útrpně.

„Ty jsi fakt pořád stejnej.“

Kryštofa těšilo, že to slyší, v určitým věku se člověk takovýho ujištění rád chytne. A taky byl rád, že Martina přišla, neposlala ho do háje, když se jí zmateně vykecával do telefonu po probdělé noci, a že můžou sedět vedle sebe na lavičce na Petříně jak stárnoucí pár, sice jím dávno nebyli, ale třeba být mohli. Dva lidi, znají se příliš dobře na to, aby jeden před druhým něco hráli, stejně se ale snesou. Vědomí, že k sobě už dávno nepatří, uhlazovalo všechny ostré hrany. Projevy vlastností a sklonů, jimiž kdysi dávno dokázali jeden druhého vytočit k nepříčetnosti, se změnily v milou připomínku starých a bezpečně minulých časů. Už tam seděli přes hodinu, ledacos si řekli. Pár drbů z pražské společnosti, jejich naprostá nicotnost jim v téhle dramatické době přišla osvěžující, probrali taky zdraví společných známých a kamarádů, téma, které s přibývajícím časem narůstá a vážní.

„Jíš dost vitamínů?“

„Žeru je jak nezavřenej.“

Se smíchem do něj strčila.

„Hele, vážně. Jak to všechno zvládáš?“

„Ale jo. To víš. Jsem většinou zalezlej, trochu mi to leze na mozek.“

Nechtěl si kazit odpoledne řečmi o tom, co přesně se mu tím mozkem honí. Zneklidňovat Martinu výklady o prorockých snech, vymítání ďábla a ztracených berlích, o krvavém šlinci na bílém rukávu a inženýrech z Veselí nad Lužnicí. O tom, že se uspává láhví alkoholu, a ani to někdy nestačí. Že se v posledních pár dnech pokoušel na internetu zjistit kontakt na všechny Pražany jménem Filipec, že pár čísel našel a postupně na ně volal pod smyšlenou záminkou a snažil se z jejich majitelů vypáčit něco, co očividně nevěděli, připadal si při tom neuvěřitelně trapně, ale stejně to zkoušel dál, k ničemu to samozřejmě nebylo. Že občas nenápadně vykoukne z okna a kontroluje, jestli v ulici není zaparkované auto, které tu dřív neviděl, a jestli vevnitř nesedí nějací lidé. Vděčně přijal šanci chvíli pobývat v Martinině neotřesitelně praktickém světě, smysl se v něm neprojevoval jako z řetězu utržená a rozum popírající síla. Spíš jako cosi neustále a klidně přítomného, nepřináší prorocké sny, ale obyčejnou starostlivost. O Evžena, je nervózní, protože musel kvůli karanténě zavřít firmu, někdy se z toho nicnedělání vztekne a začne buzerovat celou domácnost, aby měl na chvíli pocit, že řídí aspoň něco. O děti, vypadla jim škola, ale zvládají to dobře, starší dcera už u nich ani nebydlí, pronajaly si s kamarádkama krásný byt na nábřeží, jenom si to představ. O práci, ta teď stojí, ale Martina toho má hodně i tak, založila sousedskou skupinu, rozváží roušky seniorům v okolí a vyřizuje jim nákupy, aby nemuseli ven. Má dneska odpoledne pohotovost, musí být na telefonu, pro případ, že by někdo něco potřeboval.

„A roušky šiješ taky, se tě ani nemusim ptát.“

Kryštofova ironie jí vůbec nevadila, ten už jiný nebude, nemohla otřást její neokázalou sebejistotou. Tahle válka je spíš pro holky, napadlo ho. Můžou se v ní dobře uplatnit, pořádně se předvedou, jak uměj organizovat a pečovat, když se jim chce. Pro pány to je ale složitější, nemůžou patrolovat s puškou v ulicích, cítit se odpovědný za všechny doma a bejt připravený za ně umřít. Co si v takovýhle válce počít? Zvlášť když jeden není doktor a k všeobecnému úsilí by mohl přispět především svým nezvykle velkým talentem překážet. To mu pak nezbude než sedět doma, sledovat čísla a spřádat divoký teorie. Martině zazvonil telefon, rychle přijala hovor, vytáhla z kabelky propisku a zapsala nějakou adresu na okraj novin. Domluvila a usmála se na Kryštofa.

„Budu muset jít.“

„Počkej ještě moment.“

Martina se na něj usmála, teď už trochu netrpělivě. Nemá čas se vykecávat, závisí na ní další lidi, už čekají.

„Jsem se s tebou chtěl vidět taky kvůli tomu Křemenáčovupohřbu. My jsme se tam už pak nepotkali. A já jsem dost přemýšlel… Prostě jsi měla pravdu. Choval jsem se tenkrát jak kretén. Hodil jsem to celý na tebe a umyl si nad tím ruce, dotlačil jsem tě k tomu, aby ses rozhodla, a já byl přitom rozhodnutej už dávno. Rozhodnul jsem to i za tebe, jenom jsem neměl dost odvahy ti to přímo říct. Promiň.“

Martina vypadala nesvá. Třeba nestála o to, aby ji ve dnech, kdy měla všechno tak krásně pod kontrolou, připomínal chvíli, kdy kontrolu ztratila.

„To už je jedno, Kryštofe. Já pohřby těžko snášim a neměla jsem tam pít a pak to ze mě najednou vylítlo. Taky jsem pakbyla překvapená, co se to se mnou děje. Nech už to bejt.“

Kryštof se díval na její modročernou roušku, je zvláštní nevidět jeden druhému na ústa a mluvit zrovna o tomhle.

„Takžes mi odpustila?“

Martina vstala z lavičky a obrátila se k němu, teď už zjevněnetrpělivá a neklidná, na ni čeká práce, a on si zrovna v tuhle chvíli usmyslí otevírat tu starou věc.

„Odpustila. Já nevim, Kryštofe, jestli se to dá takhle říct. Je to dávno a hodně se toho od tý doby stalo. Byla jsem na tebe tehdy strašně naštvaná a dneska už nejsem. Jednou za dlouho se to připomene, nic víc. Ale většinou, vlastně skoro pořád nemyslim ani na tebe, ani na to, co mezi náma bylo. Nevim, jestli se tomu dá říkat odpuštění. Čas prostě plyne a člověk zapomíná, věci se mi ztrácej z hlavy. Některejch mi je líto. A některejch ani ne. Promiň, už fakt musim jít.“

Spěšně se rozloučili a Martina vyrazila cestou dolů na tramvaj. Kryštof se díval za ní, jak rázuje krokem ženy, která se udržuje v kondici, krokem ženy, která nutně musí být někde jinde, protože navzdory plynutí času a milosrdnému zapomnění jsou chvíle, kdy od Kryštofa potřebuje být co nejdál. Trochu se zatáhlo a ochladilo, park se zvolna vyprazdňoval. Teď si už může zapálit, už je to bezpečný. Rozvázal si roušku a vytáhl zapalovač a cigarety, natáhl do sebe kouř spolu se svěžím jarním povětřím. Začínalo se smrákat, do Kryštofa se zakusoval chlad, taky vyrazil k domovu, když se blížil k zastávce, ujistil se, že tam Martina už nestojí. Zastihl by ji tam nerad, nechtěl na ni být pověšený jak výčitka, dávná, živá a nespravedlivá, jenom by jí strašila v hlavě cestou domů.

Excerpt - Translation

So Much Ash

Ondřej Štindl

Translated into English by Graeme and Suzanne Dibble

The boy stopped in mid-run and stared silently at Kryštof. He was breathing rapidly through his mouth and a line of snot dripped slowly from his nose. His mother was approaching along the path from the children’s playground, chatting with a friend. The two well-groomed ladies in their thirties, wearing pastel-coloured jackets and matching face masks, were maintaining the prescribed distance. Prague was managing the pandemic in style – at least here in the centre, on Petřín Hill, where the locals had turned out in large numbers to enjoy the sunny spring day. Their joy at being outdoors and being able to talk to someone they knew clashed with a lingering sense of caution. Not only because of the fear of contagion, but perhaps also a concern that any undisciplined behaviour on their part would threaten the reputation of a country where the citizens were resisting the pandemic in an exemplary fashion, in spite of their abhorrent government.

This bright, colourful scene was slightly marred by Kryštof, a man with a creased face, rumpled black clothes – he hadn’t washed them for a long time and clearly wasn’t using the right detergent – and sunken eyes. Just then those eyes were focused on the three-year-old child, who looked as if he was expecting something from Kryštof, though he had no idea what that could be. So he smiled at the boy, realizing at once that it wouldn’t be visible through his face covering. He tended to feel awkward in the presence of small children, unable to drop the grown-up mask and make infantile noises with unfeigned joy. He would smile at them, that was true, but it wasn’t the kind of reflexive smile that automatically appeared on other people’s faces every time one of the little creatures laid eyes on them. Kryštof’s smiles were deliberate and laboured; he had to organize them, send the relevant instruction through the nervous system for his mouth to stretch out in the appropriate way. And kids didn’t really buy these forced displays of friendliness. The boy kept staring and Martina, who was sitting on the bench next to Kryštof, had to intervene. She shot Kryštof a look and rolled her eyes sardonically. Another useless bloke. Then she leaned over to the child and said something to him, reaching into her pocket for a cereal bar, the healthy kind with the nuts – of course it would be. The next moment the boy was running back to his mum, calling out to her loudly and enthusiastically. Martina sized Kryštof up once more in amusement.

“What’s the matter with you?”

“Nothing. I fancy a cigarette. But I don’t want to take off my face mask with all these people around. There’s always something.”

Martina laughed, a little ruefully.

“You really haven’t changed.”

Kryštof liked hearing that – at a certain age, you’re glad to cling to an assurance like that. And he was also glad that Martina had come, that she hadn’t told him where to go when he’d blabbered incoherently to her on the phone after a sleepless night, and that they could sit next to each other on a bench on Petřín Hill like the ageing couple they hadn’t been for a long time but perhaps could have been. Two people who knew each other too well to put on a front but still got along anyway. The awareness that they hadn’t belonged to each other for a long time smoothed out all the rough edges. Signs of character traits or habits that would once have driven the other person to distraction had become a touching reminder of old and safely bygone times. They’d already been sitting there for over an hour and had told each other all sorts of things. A few snippets of gossip from Prague society, whose utter triviality seemed refreshing in these turbulent days, and they also discussed the health of mutual acquaintances and friends, a subject that grew in size and importance as time went on.

“Are you taking plenty of vitamins?”

“I’m guzzling them as if they were going out of fashion.”

She elbowed him, laughing.

“Hey, seriously. How are you holding up?”

“Yeah, all right. You know. Most of the time I’m cooped up in the flat, it’s getting to me a bit.”

He didn’t want to spoil the afternoon by talking about what was really on his mind. To disturb Martina with explanations about prophetic dreams, exorcisms and lost crutches, about a bloody streak on a white sleeve and graduates from Veselí nad Lužnicí. About the fact that he needed a bottle of booze to get to sleep, and sometimes even that wasn’t enough. That in the last few days he’d been scouring the internet for contact details for anyone in Prague by the name of Filipec, had found a few numbers and had been calling them one by one under a false pretext, trying to coax information out of strangers that they clearly didn’t know, finding the whole thing incredibly awkward but keeping at it anyway, useless though it was. That from time to time he would surreptitiously peek out of the window to check whether there was a car parked in the street that he hadn’t seen there before, and whether there were people sitting in it. He was grateful for the chance to spend some time in Martina’s unshakeably practical world, where purpose didn’t take the form of a rampaging, logic-defying force. Her version of purpose was something constantly and serenely present – instead of prophetic dreams, it manifested itself in ordinary concern. Concern for Evžen – he was on edge because he’d had to close the business due to the lockdown; at times all that sitting around put him in a foul mood and he started bossing the whole family about, just so he could feel he was in charge of something for a while. Concern for the children – their classes had been cancelled, but they were coping fine; their older daughter was no longer living with them anyway, she was renting a lovely flat with her friends on the embankment, can you imagine. And concern about her job – that was on hold, but Martina had her hands full as it was: she’d set up a neighbourhood group that distributed face masks to elderly people in the area and did their shopping for them so they didn’t have to go out. She was on call this afternoon; she had to keep her phone handy in case somebody needed something.

“And of course you sew face masks too – I don’t even have to ask.”

Kryštof’s sarcasm didn’t bother her in the slightest; he was never going to change. It would take more than that to shake her quiet confidence. This is a war for the girls, he thought. It allows them to put their skills to use and show off how good they are at organizing and caring when they want to be. But it’s more complicated for the men – they can’t patrol the streets with a rifle, feeling responsible for everyone at home and ready to die for them. What are they supposed to do in a war like this one? Especially if you aren’t a doctor and the main thing you can contribute to the general effort is your special talent for getting in the way. Then the only option you have left is to sit at home, tracking the numbers and concocting wild theories. Martina’s phone rang and she quickly answered, pulling a pen out of her handbag and writing down an address on the edge of the newspaper. She ended the call and smiled at Kryštof.

“I have to go.”

“Hold on a second.”

Martina smiled at him again, a little impatiently this time. She didn’t have time to shoot the breeze; other people were depending on her, and they were already waiting.

“I also wanted to see you because of what happened at Křemenáč’s funeral. We didn’t bump into each other again. And I’ve been doing a lot of thinking… Basically, you were right. I acted like a jerk back then. I dumped it all on you and washed my hands of it. I pushed you into taking the decision when my mind was already made up. I decided for you as well, I just didn’t have the guts to say it to your face. I’m sorry.”

Martina looked uncomfortable. Perhaps at a time like this, when she had everything nicely under control, she didn’t like being reminded of a moment when she had lost control.

“It’s water under the bridge, Kryštof. I’m not good with funerals and I shouldn’t have been drinking there and all of a sudden I just came out with it. I surprised myself too. Just forget it.”

Kryštof gazed at her blue-and-black face mask – it was strange not to see each other’s mouths when talking about a subject like this.

“So you’ve forgiven me?”

Martina got up from the bench and turned towards him, now visibly impatient and restless – she had work to do and he had to go and choose a moment like this to reopen old wounds.

“Forgiven you... I don’t know, Kryštof, if you can put it like that. It was a long time ago and a lot has happened since then. At the time I was really angry at you and now I’m not. Every once in a while something reminds me of it, that’s all. But most of the time – in fact, pretty much all of the time – I don’t even think about you or what happened between us. I don’t know if you can call that forgiveness. Time goes by and things get forgotten, they fade from my memory. Sometimes I regret that. And sometimes I don’t. I’m sorry, I really do have to go.”

They said a hasty goodbye and Martina set off down the hill to catch a tram. Kryštof watched her go, striding along with the brisk step of a woman who keeps herself in shape, a woman who urgently needs to be somewhere else, because despite the passage of time and the mercy of forgetting, there are moments when she needs to be as far away from Kryštof as possible. It was starting to turn cloudy and cool, and the park was slowly emptying. He could light up, it was safe now. He untied his face mask and pulled out a lighter and cigarettes, drawing in the smoke along with the crisp spring air. The light was fading and the cold was nipping at Kryštof, so he headed for home too. When he got near the tram stop, he checked to make sure Martina was no longer standing there. He wouldn’t have liked to have caught up with her, didn’t want to hang around her like an unfair living reproach from days long past that would only have haunted her on the journey home.