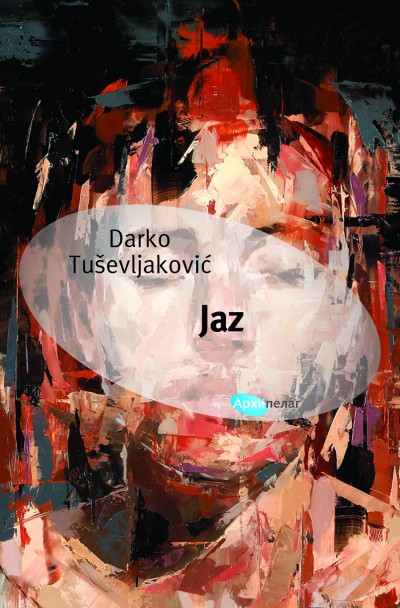

Darko Tuševljaković est né à Zenica, en Bosnie-Herzégovine, en 1978. Il vit et travaille à Belgrade. Depuis 2002, ses œuvres de fiction ont été publiées dans des magazines et anthologies en Serbie et ailleurs dans les Balkans. En 2004, il a reçu le Prix de la nouvelle Lazar Komarcic. Tuševljaković a écrit deux romans et un recueil de nouvelles. Ses livres ont été sélectionnés pour certains des plus importants prix littéraires nationaux de Serbie. En 2016, son roman Jaz (traduit en anglais : The Chasm) a été sélectionné pour le prix NIN, le plus prestigieux prix littéraire serbe, décerné au meilleur roman de l'année.

Agent / Rights Director

Publishing House

Translation Deals

- Albania: Albas

- Bulgaria: Uniscorp

- Greece : Vakxikon Publications

- Italy: Voland SRL

- Poland: Ezop

- Slovenia: Sodobnost International (Reading Station project)

- English: Dalkey Press

- Romanian: Editura Minerva

- Spanish: IPC Media, part of IPC d.o.o. Beograd

Excerpt

Translated by Randall A. Major and Ema Pandrc

Even after all those years, Bogdan was awakened by a bang. This time his pupils exploded and, when he came to his senses, he felt his eyelids with the tips of his fingers to make sure that there was still something lying under them. He was fairly satisfied with his conclusion: he was occupying all three dimensions, and the fourth was gradually coming back to him as he tossed and turned in an uncomfortable bed he had never slept in before. An old man knows he’s alive when every inch of him hurts, it occurred to him. And in the same way, he’s able to separate the dream world from the waking one. In his dreams, no matter how nightmarish, pain doesn’t exist. It only comes later, on this side of the wall, it starts and ends here. Pain pervades length, width, and height, and lasts for seconds and ages. That thought was supposed to be a consolation because it meant that all the horrors one dreams are harmless, but it didn’t make Bogdan feel any better. With his palm he rubbed his nose, which was itchy from his snoring, then raised his eyelids and for a moment was blinded. Radica had already opened the jalousies and a glimpse of the blue sky threatened to actually dig out his eyeballs. He felt dried sweat on his skin, the swollen mosquito bites were burning. It was difficult to choose a dimension suitable for escaping.

“At least close the curtains,” he mumbled.

The suite in which they had spent the tortuous night smelled of a lotion that dizzied them; they had been forced to buy it as soon as they unpacked the previous evening, because the services didn’t include safety from the little bloodsuckers. The island they were visiting was not sprayed, ostensibly to protect the olive orchards, but no one put screens on the doors and windows. That is why every shop they entered, spotty like typhus victims, had a special rack with anti-mosquito products, the cheapest of which cost 15 euros. Greek bastards.

Radica was heating water on an old greasy hot plate. The smell of coffee mingled with the smell of the insecticide lotion, and Bogdan threw the sheet back and rushed straight from the bed onto the terrace.

Nothing about the suite was good, it was where physical and spiritual pain connected. Damir had recently explained to him how reality enhancement computer programs work and showed him what they can do, for example, with an old photograph from his army days; but when Radica and Bogdan were in the agency choosing their lodgings it never even crossed his mind that none of the luxuries in the fancy presentations would actually be there when they arrived. Squalid, that was the right word for it. Everything was squalid. The beds were creaky and slid too easily across the tiles laid even in the bedroom, as if it were a slaughterhouse, and not a hotel suite. The kitchen was so cramped that you could hardly open the refrigerator, and there were no pots among the dishes. What were they thinking, how was one supposed to eat? There were no pots, but there was an egg cutter in the cabinet above the sink. (Bogdan didn’t know exactly what the thingy was called, so he called it a cutter. That little piece of crap with wires that you push down over an egg to cut into slices. Into wedges. Whatever… Who needs that?) And a teapot. They had supplied all sorts of special utensils, but they had forgotten the general-purpose stuff – like a pot in which you could make tea and boil an egg. As soon as they arrived, Radica had told him why it was so, but Bogdan was not satisfied with the explanation. How could she know? It also did not seem real to him that all of Corfu, including Dassia where they were staying, was primarily visited by tourists from Western Europe, mostly from England and Holland. “So, where are all the Brits?” he asked, pointing at the surrounding suites which were occupied to the last by Serbs. The second they got off the bus, several passengers had jumped straight into the pool and their host, a middle-aged slouching Greek in whose eyes Bogdan saw only money, money, money, began shouting at them and made them get out of the water. The confused travelers milled around the deserted restaurant waiting for their room keys, only to be marched to their rooms single file, like prisoners. “So where are all the Brits?” he had said then as well, leaning on the built-in barbecue in the closed-up dining hall, while Radica was straightening up the pile of luggage. He ran his finger over the grill and showed her that it was perfectly clean. “Nobody has used this for months. Years even.” Radica just shrugged. “That’s because the Brits don’t come here anymore. See, the kitchen isn’t even open. They won’t light the fire for people like us.” She picked up the smaller suitcase and instructed him with a look to take the bigger one. “That’s probably why we’re also not allowed in the pool,” she added, heading off in front of him to the suite. English bastards, he thought.

On the terrace, he was swept by a warm wind that gained speed as it came down the mountainside towards the sea. It smelled of… chlorine from the pool. Bogdan shook his head and crossed his arms. Why did they decide to come in the first place? Why had he agreed to a summer vacation in the high season, in the period he had always avoided even while he was in the service – and it had been a lot harder back then to go on vacation exactly when you preferred to. His superiors, truth be told, had usually yielded to his choices. Captain Bogdan, a.k.a. the God-Given, they would say and write the dates he had picked into the calendar. Captain God-Given can go on vacation whenever he desires. What he could not do was to be promoted to the rank of major, but Bogdan had stopped thinking about that long before he retired. He had never really been obsessed with ranks. Promotions in the workplace were Radica’s thing, but she was cursed and Bogdan knew that. Even now – coffee was threatening to ruin his day. The coffee, the mosquito lotion, the chlorine, the egg cutter, the teapot, the non-existent Brits, the greedy Greeks, the whole island way too close to Albania.

It was her idea. She told him that they should get out of Belgrade, at least for a week. And he believed the given solution would work, just like he believed Damir that Photoshop can change people’s appearances. Only that’s not true: people change themselves, they make freaks of themselves. They don’t need a computer program for that. If he could leave, so can we, he thought at the time and let Radica choose the destination. She chose the seaside, of course. Corfu, she said, where the yellow lemon blossoms. With the passing of time, he had come to understand what a peculiar kind of people are those who come from the karst regions. Nothing can be compared with the thinking of someone who spent their whole childhood surrounded by greyness. The stones from the bare mountains threaten to move into a man, filling him like the wolf in the fable of the seven little goats, and dragging him to the bottom. Bogdan didn’t think that Radica had reached the bottom, because he didn’t know where that bottom was supposed to be. He was even more frightened by the thought that there was no bottom at all. He began to wonder whether everything the two of them did, those long-since established patterns in which they moved closer to or further away from each other, was mere groping in a dream devoid of dimension and meaning.

The anti-mosquito lotion smelled like lemons. Now even the coffee smelled like that, too. So much for the famous Corfu. Everything is fake nowadays. People are fake, smells are fake, islands are fake, no matter how big the humps on their backs. Humps that block the sun. Pantokrator. Who gives a mountain a name like that? Sounds like farm machinery. Radica, I’m gonna go plow the field with the pantokrator.

Bogdan stared out at the sea, about half a kilometre away from the complex and swimming pool. In the distance, towards Albania, it sparkled in the sunshine as if covered in cellophane, but the shallows of Dassia were in the shade. Bogdan didn’t feel like swimming in the cove where the wind rippled the water; it seemed cold, and the sand shining white at the bottom could have been quicksand, waiting to swallow a man whole. If Radica was to be trusted, nobody would drag him out, because the locals would not understand him, despite their traditional Greek-Serbian friendship. He’d cry out: “Upomoć!” and not “Help!” or “Hilfe!” When it finally did peek out from behind Pantokrator, the sun would be broiling hot and Bogdan would suggest not to go down to the beach today. They were too tired from travelling anyway. In the evening, they could take a walk around town, but nothing more than that. He was not a man of stone. He was born in the fields, he came from the fertile land of Šumadija which, in all honesty, most often made him neither smarter nor gentler. When they’d first met, they joked that the differences between them would improve their relationship, that those things would bring them even closer together in what they shared. Perhaps it was true sometimes but, like when the boundaries of their common dreams were in question, Bogdan was more often disturbed by the thought that there were no similarities or agreements.

“We should be in the common room in half an hour,” Radica called out from the room, sipping her coffee. “The tour operator is coming to tell us about the arrangements. There are some outings, I saw them on the bulletin board. Paxos, Antipaxos. There’s one to Vido as well. Maybe…”

“Maybe we could just skip all that prattle,” Bogdan said, turning his back to the sea. He was met by a view of the slopes and a wind which drove straight into his face. Again he felt pressure in his eyes, a sign that something within him was about to burst. He knew that he was being defiant in vain. He went into the room, holding his breath so that he could avoid the unpleasant smells. He shut himself up in the bathroom and changed into decent clothes. When Radica had finished her coffee, they went downstairs. There, several guests had already gathered around the barbecue and the unset dining tables, and Radica recognized a couple who had been sitting across the aisle from them on the bus from Belgrade to Corfu. During the rest stop near Predejane, she had exchanged a few words with them, while Bogdan relieved his bladder at the motel. When the bus had left the parking lot, she told him their names were Tanja and Zoran Simović, and that they too were headed for Dassia. The gentleman was even retired from the military, like Bogdan. “How nice,” he said, closing his eyes to avoid getting nauseous. Now, as he was standing among the sleepy tourists, waiting for the tour operator, he realized that that had been the first sign: a warning that they should have stayed at home. But he hadn’t recognized it at the time and now it was too late. Radica was already chatting with that Zoran fellow and his significantly younger spouse, waving Bogdan over with her purse, to which he gave a wave of his hand and sat at the table right in the middle of the room at a safe distance from them. Radica soon joined him with a map of Corfu which her new acquaintances had given her.

“I mean, really…” she swung her purse as if she were about to box his ears with it. “They’re staying in the suite next to ours. We’ll be running into them all week. Why don’t you relax for a change? That’s why we’re here, right?”

“No, that’s not why we’re here,” Bogdan replied, knowing that would shut her up. Still, he was examining the inside of her purse, which always reminded him of an ugly and ill-trained dog, ever ready to start barking. It had a surly snout and, whenever Radica unsnapped its metal jaws, Bogdan was afraid that a deluge of bile would come at him which its owner had stored in the darkness of its leather bowels. Fortunately, now it seemed to him that there was no reason to dread such niceties. The secrets in that purse were kept safe, hidden behind her mocking facial expression.

| Élément joint | Taille |

|---|---|

| EUPL_2017_RS_Darko_Tusevljakovic.pdf | 331.13 Ko |