Gabriela Ruivo vit à Londres depuis 2004. Elle remporte le Prémio LeYa en 2013 pour son premier roman, Uma Outra Voz, qui est également couronné du Prémio PEN Clube Português Primeira Obra (ex-aequo) en 2015, et qui paraît au Brésil en 2018 (LeYa – Casa da Palavra). Ses autres ouvrages comprennent le recueil de poèmes Aves Migratórias (On y va, 2019), Espécies Protegidas (nouvelles, On y va, 2021), et Lei da Gravidade (son dernier roman, Porto Editora, 2023). Elle a traduit La Case de l’oncle Tom (A Cabana do Tio Tom) de Harriet Beecher Stowe de l’anglais vers le portugais (Sibila Publicações, 2020). Elle dirige Miúda Books, une librairie en ligne qui se spécialise dans les livres pour enfants rédigés en portugais, ainsi que le Conseil Culturel de l’Association Internationale des Lusodescendants au Royaume-Uni, où elle a fondé le club de lecture PinT – Portuguese in Translation, qui se réunit tous les deux mois sur Zoom pour converser autour de différents livres, écrits par des auteurs de langue portugaise et traduits en anglais. Elle est membre du Clube das Mulheres Escritoras (« Club d’autrices »), une initiative cherchant à promouvoir les œuvres d’autrices portugaises contemporaines.

Que partagent un vieillard sur son lit de mort à l’hôpital, l’auteur d’un bestseller, un préadolescent agité et un enfant de deux ans ? Quel destin attend Maria Ana et Ana Maria, qui sont le reflet l’une de l’autre ? Est-ce que l’une d’entre elles pourra se débarrasser d’un mari violent, et l’autre de la douleur d’une perte ? Qu’en est-il de Marinela ? et de Mariana ? Qu’en est-il de la mère célibataire qui existe dans chacune d’entre elles ? et du père au centre de cette catastrophe ? Qu’en est-il de l’avenir, qui s’acharne à devenir le passé, et du passé, qui s’acharne à devenir l’avenir ?

Le temps représente le grand mystère, qui se moque de nous derrière un miroir scruté pour trouver le sens de la vie, mais qui ne rend qu’une image de l’absurde. C’est également le temps qui perpétue un motif de violence, la même histoire qui se voit répétée, contre l’espoir du lecteur que le cycle sera enfin arrêté.

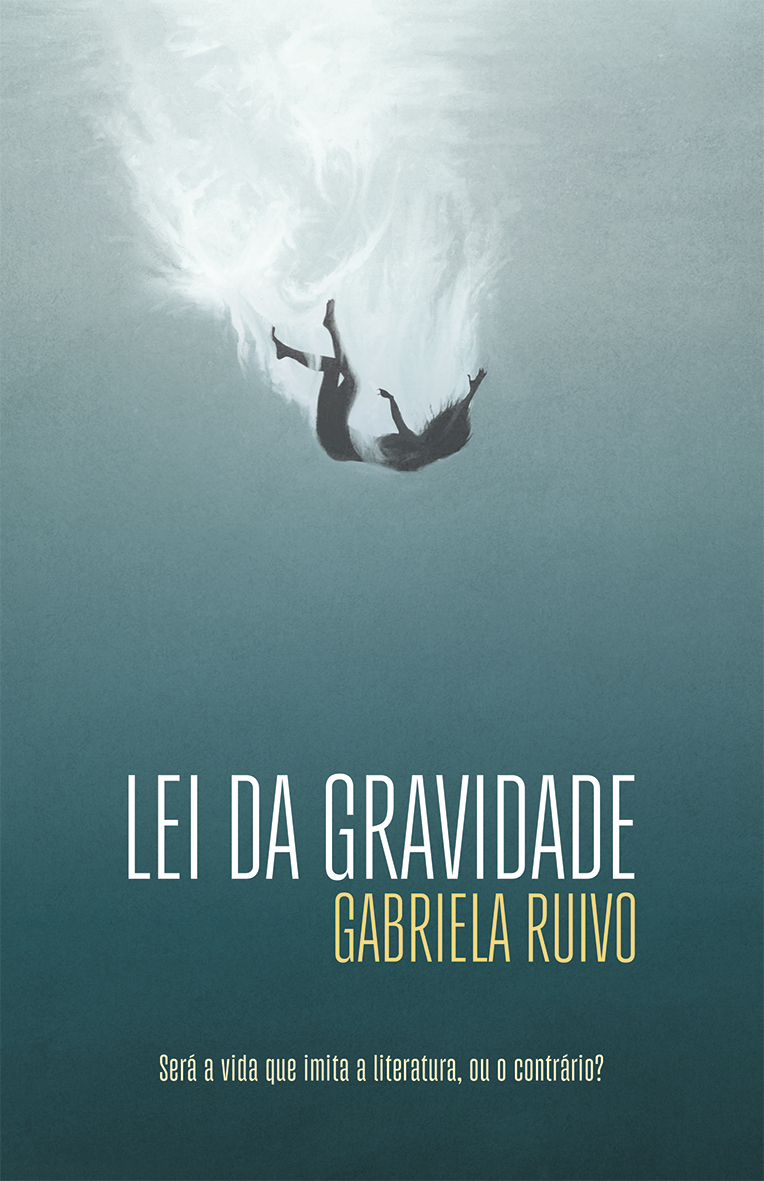

Ce roman propose un univers alternatif dans lequel le temps est soumis à la loi de la gravité – la force motrice qui réunit le passé, le présent et le futur, et dissout les contours de la réalité. Il nous invite à découvrir d’autres mondes au sein des concepts du temps et de l’espace et, finalement, de la littérature elle-même.

Agent / Rights Director

Publishing House

Excerpt

A jornalista

Decididamente, isto não está a correr bem.

Ficara exultante com a proposta do chefe de redacção para entrevistar Luís Ricardo Reis, o último escritor-revelação, um fenómeno literário como há muito não se via no país, porventura como nunca se vira. Tinha ali a oportunidade de fazer, ela também, a sua reportagem-revelação. Era um mundo cão, este; tão poucas as histórias realmente interessantes, aquelas que poderiam fazer história. Um mundo de micro-histórias, micronotícias, a maioria desinteressantes, nada de novo a anunciar, porque a quantidade de novidades por minuto era tal, que tudo expirava rapidamente, as calamidades sucediam-se, as naturais e as outras, já nem as bacoradas que saíam da boca do Presidente dos Estados Unidos surpreendiam; o mundo perdera a capacidade de se espantar, de se maravilhar, de se indignar, de se ofender, embora parecesse o contrário, as emoções ao rubro, as queixas de ofensas e assédios a multiplicarem-se como nunca se vira, as mulheres a ganharem voz, uma multidão aos gritos, mas no meio de gritos ninguém se entende e rapidamente deixamos de ouvir o essencial ou de prestar atenção ao que é importante. Como manter o foco da atenção nos dias que correm, aí estava uma boa questão, e um tema suculento; mas, hoje em dia, as pessoas não querem ler matérias suculentas, isso dá muito trabalho, as notícias querem-se como as fotografias, flashs de palavras que eternizem uma ideia, poucas, pensar é cansativo, ler parágrafos intermináveis ainda mais, tudo tem de ser de digestão leve, abertura fácil, poucas calorias, mínimo esforço mental. Amanhã ninguém se lembra dos títulos das primeiras páginas dos jornais de hoje, a não ser que sejam acerca de algo verdadeiramente drástico e surpreendente, o que, nos dias que correm, é praticamente inexistente. Um jornalista está condenado a ver as suas histórias votadas ao esquecimento colectivo, engolidas pelo buraco negro da avidez da novidade; e para quê investir num tema, numa ideia, escrever o que quer que seja, se amanhã já ninguém se lembra? Quem sabe não era essa a essência do jornalismo? Porque afinal as notícias passam, ficam para trás, assim como as coisas acontecem e nós as esquecemos, e só retemos na memória algo considerável ou extraordinário. O permanente é do teor do ensaio ou da literatura. Mas ainda há temas jornalísticos que criam impacto suficiente para se imporem, persistirem, ficarem para os anais da História. Ela sempre acreditara nisso e mantinha a fé, com a vontade de escrever a tal peça, a que ficaria para a posteridade, a que seria lida e relida e lembrada e apontada como exemplo. Não, não era ingénua a ponto de acreditar que uma simples entrevista pudesse ser essa peça, por mais famoso que fosse o entrevistado. Mas poderia ser o primeiro passo. Uma primeira matéria digna de nota, que continuaria a fazer eco nos dias seguintes. No início da entrevista, ficara entusiasmada, o homem debitava ideias com a habilidade de um mestre, ela tinha ali matéria para muito, uma entrevista-reflexão, uma entrevista- -ensaio, tantas ideias loucas lhe passaram pela cabeça, uma matéria sobre o propósito da literatura, os leitores que gostam de ouvir histórias desde que não as encontrem nos livros, porque nos livros procuram a verdade; os livros como espelhos, capazes de reflectir uma identidade, a identidade como pedra basilar da coesão social, a crise identitária como directriz principal da crise de valores. Tinha ali matéria para brilhar. Fosse ela capaz de retirar o imediatismo à entrevista, transformá-la em matéria de reflexão, em porta aberta para a conceptualização e exercício do pensamento, sem carregar demasiado na tecla intelectual, para não se tornar cansativo. E quando o homem confessara que, afinal, o livro que escrevera era baseado na sua vida, que era a descrição pura da realidade, ela exultara; além do convite à reflexão, tinha outra tese, inteiramente nova, para desenvolver: que a literatura é, na essência, a própria vida. Escreveria de forma arrojada, omitiria as perguntas; apresentaria a entrevista como uma espécie de monólogo interior, um jogo de pergunta-resposta que não obedeceria ao guião, antes ao fluir das ideias do escritor, misturadas com recordações da sua vida; habitaria os pensamentos dele, atrever-se-ia a entrar-lhe para dentro da cabeça, apoderando-se das suas ideias, numa técnica inovadora, uma escrita distanciada do modelo clássico da entrevista e mais próxima da reflexão de um narrador indefinido, um narrador que se funde com o objecto narrado. Debatia-se já com o esquema mental da peça, numa antevisão detalhada de pequenos detalhes técnicos e linguísticos, quando aquela sensação tomou conta de si…

Era uma sensação antiga.

Talvez tivesse sido o tom da voz dele. Aquele toque de impaciência. Os olhos a revirarem-se. O modo como parecera dar-lhe uma lição, como se fizesse um frete, como se tivesse de explicar tudo, e que maçada, porque ela, a coitadinha, a burrinha, não entendia, claro que não. E, nessa altura, o seu cérebro bloqueara, quisera fazer perguntas inteligentes, dizer coisas que viessem a propósito e que demonstrassem a sua clarividência, e nada. Sentira-se burra e actuara como tal. Sabia disso. Tinha perfeita consciência de si própria. Desde criança. Os homens da sua família sempre a tinham feito sentir-se assim. O avô, o pai, o tio. A verdade é que nunca fora uma aluna brilhante. Sempre se esforçara bastante, mas na família reinava a crença de que a verdadeira inteligência é aquela que se apresenta como um prodígio, sem necessidade de esforço, como se a criança tivesse sido abençoada por uma fada madrinha. A outra, a que se consegue à custa do esforço e do trabalho, nunca seria a mesma coisa.

Por isso, vivia à espera da oportunidade de brilhar. De mostrar a todos a fibra de que era feita. Que, afinal, estavam enganados; ela nascera com a estrela na testa, mas, por qualquer motivo, esta não se dispusera a brilhar de forma espontânea. Sim, ainda haveria de os ver engolir a soberba, as manias de superioridade.

E o homem falava, imparável, e ela distraíra-se, espero que esta porcaria não se lembre agora de avariar, o que seria dela se perdesse aquele material? O homem falava e ela permanecia em silêncio, sem saber o que dizer; precisava de intervir, fazer um comentário, uma pergunta que direccionasse a conversa noutro sentido; ele discorria sobre a morte da mulher e do filho, sobre a fase mais negra da sua vida, e ela sentia a escuridão apoderar-se da sua mente, uma maré negra a alastrar, asfixiando a vida marinha, tingindo o verde das águas de luto e desolação; não se podia deixar arrastar para o fundo, havia que se manter à tona, nadar para longe, respirar, não deixar que o petróleo lhe inundasse os pulmões. O homem é um poço de energia negativa, pensou, com um arrepio, se não reajo, vou ficar infestada, vou perder forças, discernimento, não conseguirei alinhavar dois pensamentos. Vou interrompê-lo, vou dizer qualquer coisa, agora, mas nada lhe saía da boca, nenhum som, como se de facto os pulmões se tivessem intumescido de uma matéria viscosa – ou seriam os neurónios?

Não, isto não está a correr nada bem.Excerpt - Translation

Translated into English by Victor Meadowcroft and Andrew McDougall

The Reporter

This certainly isn’t going well.

She had been thrilled by the chief editor’s proposal that she interview Luís Ricardo Reis, the latest breakout sensation, a literary phenomenon unlike any that had been seen in the country for quite some time, if ever. She found herself presented with the chance to produce a breakout article of her own. It was a dog-eat-dog world they were living in; so few really interesting stories, ones that could make history. A world of micro-stories, micro-news items, the majority of them uninteresting, nothing new to report, because the quantity of news stories per minute was such that everything expired quickly, disasters took place – both natural and otherwise – and now not even the drivel coming from the mouth of the President of the United States could surprise anyone; the world had lost its capacity for shock, for wonder, for indignation, for taking offence, although it seemed the opposite was also true, flared emotions, accusations of abuse and harassment multiplying like never before, women had gained a voice, become a baying crowd, but in the midst of an uproar no one can understand each other and we soon stop hearing the essential or paying attention to what’s important. Like how to maintain focus in these times we’re living through: now there was a good subject, a juicy topic. But these days people no longer want to read about juicy topics – it's too much work – people want articles like photographs, a flash of words that will eternalise an idea – very few words, because thinking is tiring, and reading interminable paragraphs even more so – everything must be easy to digest, accessible, low on calories, minimal mental exertion. Tomorrow, no one will remember the headlines of today’s newspapers, unless they’re about something truly dramatic and surprising – practically non-existent in this day and age. A reporter is condemned to watch their stories be cast into collective oblivion, swallowed by the black hole of yearning for the new. And why invest in a topic, an idea, why write anything at all, if by tomorrow no one will remember? Perhaps that was the essence of journalism? Because, ultimately, the news moves on, stories get left behind, just like the things that happen to us and are forgotten, our memory only retaining something if it’s substantial or extraordinary. The permanent is the substance of essays or literature. But there are still journalistic themes that cause enough impact to matter, to last, to earn their place in the annals of history. She had always believed this and maintained her faith, with a hunger to write such a piece, one that would last for posterity, one that would be read and reread and remembered and cited as an example. No, she wasn’t naïve enough to believe that a simple interview could become this piece, no matter how famous her interviewee. But it could be a first step. A first, noteworthy article that would continue to reverberate over the days that followed. At the beginning of the interview, she’d been excited, the man put forward ideas with the skill of a master, there was plenty of material there, for a reflective-interview, an essay-interview, so many crazy notions went through her mind, an article about the purpose of literature, about readers who enjoyed listening to stories as long as they didn’t find them in books, because books were where they went looking for truth; books as mirrors, capable of reflecting an identity, identity as the cornerstone of social cohesion, the identity crisis as the main driving force of the crisis of values. She had enough material there to shine. If she could eliminate the immediacy of the interview, transform it into material for reflection, an open door for conceptualisation and contemplation, without leaning too hard on the intellectual side, so as not to become tiresome. And when the man confessed that, in fact, the book he’d written was based on his own life, was a pure description of reality, she was overjoyed; aside from the invitation to reflect, she now had another thesis – an entirely new one – to develop: in essence, literature is life itself. She would write in a bold style, omitting the questions completely; she would present the interview as a kind of interior monologue, a game of questions and answers that didn’t follow a script but instead the flow of the writer’s ideas, mixed with recollections from his life; she would inhabit his thoughts, venture inside his head, taking possession of his ideas, in an innovative approach, a text distanced from the classic interview model and nearer to the reflections of an undefined narrator, a narrator who fuses with the narrated object. She was already wrestling with the conceptual model for the piece, a detailed preview of the technical and linguistic details, when that feeling came over her…

It was an old feeling.

Perhaps it had been his tone of voice. The hint of impatience. That rolling of the eyes. The way he seemed to be giving her a lesson, as if carrying out a laborious task, as if he needed to explain everything, and what a drag, because she – the poor thing, the bimbo – didn’t understand, of course she didn’t. And at that point her brain had frozen, she had wanted to ask intelligent questions, to say things that were relevant and demonstrated her perceptiveness – but nothing. She had felt stupid and acted accordingly. She realised this. She was perfectly self-aware, and had been ever since she was a child. The men in her family had always made her feel this way. Her grandfather, her father, her uncle. The truth is, she had never been a brilliant student. She always tried very hard, but in her family the belief prevailed that real intelligence presents itself in the form of a prodigy, with no need for effort, as if the child had been blessed by a fairy godmother. The other kind, attained through effort and hard work, would never be the same.

This is why she lived in expectation of her chance to shine. To show everyone the stuff she was made of, and that, in the end, they were all wrong: she had been born with the star on her brow, but for some reason it had failed to spontaneously burst into light. Yes, she would live to see them swallow their pride, their air of superiority.

The man talked incessantly and she became distracted, I hope this piece of junk doesn’t decide to stop working – what would become of her if she lost that material? The man talked, and she kept silent, not knowing what to say; she needed to intervene, make some comment, a question that would lead the conversation in another direction; he spoke about the death of his wife and son, about the blackest period of his life, and she could feel the darkness taking hold of her mind, a dark tide spreading, suffocating the marine life, tinging the green waters with grief and desolation; she couldn’t allow herself to be dragged to the bottom, she had to stay afloat, to swim far away, breathe, not allow the petroleum to flood her lungs. This man is a well of negative energy, she thought, with a shudder, if I don’t react, I’ll become infested, I’ll lose my strength, my judgement, I won’t be able to string two thoughts together. I’m going to interrupt him, I’m going to say something, now, but nothing came out of her mouth, not a single sound, as if her lungs were in fact swollen with viscous material – or was it her brain cells?

No, this isn’t going well at all.